Published April, 2017 by Jackie Zammuto in Update

Human Rights in Western Sahara – A year in review

Watching Western Sahara curates and contextualizes eyewitness videos filmed by citizen journalists in the Morocco-occupied Western Sahara, a territory off-limits to most human rights monitors and international media. This report summarizes our main findings after one year of curating footage.

Each April, the UN Security Council votes to renew its peacekeeping mission in Western Sahara, a territory under Moroccan occupation for 41 years. And each year, human rights groups call for the mission to not only be renewed, but extended to include human rights monitoring as part of its mandate. “Enabling the UN peacekeeping mission to monitor human rights in Western Sahara and the Tindouf refugee camps is crucial for ensuring that abuses committed far from the public eye are brought to the world’s attention,” stated Amnesty International this week.

It is one of the rare times that human rights in Western Sahara, often dubbed Africa’s last colony, is examined on an international stage.

Given the current absence of UN human rights monitoring in the Western Sahara, the control of the press by Morocco, the banning of international human rights organizations, and the frequent expulsion of journalists and international observers, there is very little documentation to scrutinize to understand the state of human rights under Moroccan occupation. The paucity of video reports, news articles, and documentary films that could provide a window into life in the territory is astonishing. And it may be one reason the Security Council continues, each April, to decline calls by Sahrawis and international advocates to implement its own human rights monitoring system. Out of sight, out of mind.

Citizen Journalists Provide Rare Documentation

Yet there is one source of documentation that exists: Sahrawi citizen journalists, who surreptitiously film protests and abuses in the occupied territory and share their videos online for the world to see. Using their footage as a basis of documentation, Watching Western Sahara is publishing our first annual report on human rights in Western Sahara. Covering April 2016 through March 2017, we have reviewed eyewitness videos from citizen journalists during roughly the timeframe of the UN mission in Western Sahara (MINURSO), which is up for its yearly extension by the Security Council this month.

In the context of a near vacuum of foreign correspondence, United Nations monitoring, and on-the-ground research by international human rights organizations, videos by citizen journalists provide a critical window into the social movements taking place on the streets of Western Sahara and attacks on voices of dissent.

Since last year, we have monitored videos taken at risk by Sahrawi media activists, independent reporters, and citizen journalists, and curated them on the Watching Western Sahara platform. Individually, the videos show disturbing scenes of protests and repression within a police state. Collectively, they portray stories of widespread social upheaval and patterns of abuse that Morocco doesn’t want the world to see.

Below is an overview of some of the main human rights issues documented in eyewitness videos from April 2016 through March 2017. For more on any of the issues or videos covered in this report, or for updated reporting, go to Watching Western Sahara. At the end of this report is an explanation of our research methodology.

Overview of Human Rights Issues Seen Through Eyewitness Video

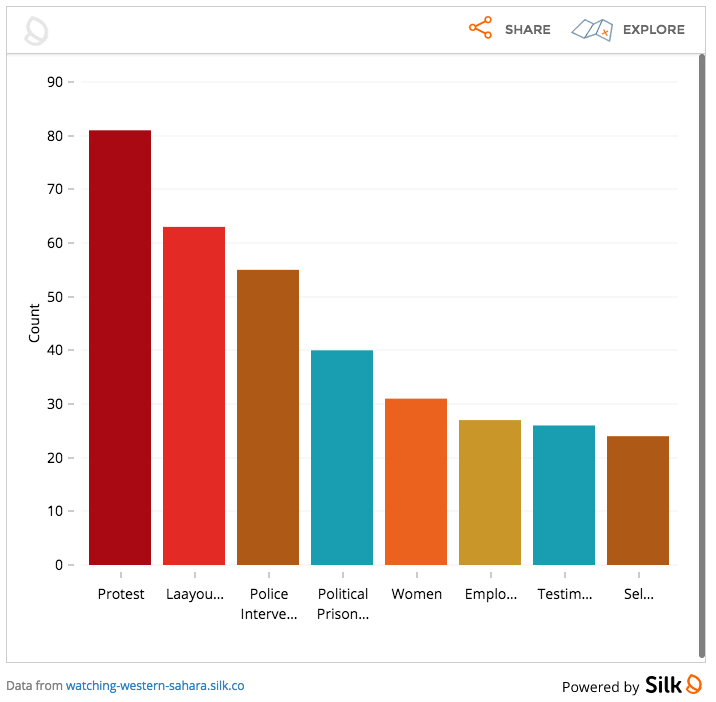

Between April 1, 2016 and March 31, 2017, we curated 111 videos. The majority (80) document protests, which ranged from 4 people to several hundred. Other videos included testimony (26) — from international observers or from witnesses, victims, and survivors of human rights abuses.

While the majority of protests captured in curated videos (50) took place in Laayoune, the capital of Western Sahara, many took place in other cities throughout the occupied territory: six in Smara; one in Bou Craa, a center of controversial mining operations; two in the southern city of Dakhla; and three in the coastal city of Foum el-Oued, the site of a women’s march that was brutally attacked in November.

We also curated several videos of protests in Morocco. Two were in Guelmim, a city in southern Morocco with a large Sahrawi population that has protested for the rights of Sahrawi people living in Western Sahara and Morocco. Sahrawi demonstrations have also taken place in Salé, near the Moroccan capital of Rabat. Salé is the site of a new trial for a high-profile group of Sahrawi political prisoners who have been behind bars since 2011.

The frequency and variety of mass demonstrations across Western Sahara paint a picture of widespread social upheaval that contrasts with the narrative the Moroccan state often portrays to the international community, captured in this quote from Morocco’s declaration to the UN Human Rights Committee last summer: “Morocco does not interfere in any way with the enjoyment by the people of the Moroccan Sahara of their political, civil, social and economic rights.” Every week, in fact, the Sahrawi people express their grievances in regards to the violations of those rights, and, as we document below, their calls are consistently repressed.

Freedom of Assembly & Expression

While the human rights issues spotlighted in protests are diverse, there are two common themes to the protests: nonviolence, and police intervention.

None of the protest videos we saw or curated show Sahrawi protesters incite violence. In many videos, demonstrators march, in others, they stand in the street with a banner and chant. Those organized by unemployed activists calling for better job opportunities for Sahrawis are often distinguished by the colored vests the demonstrators wear. In others, the protest is clearly designed for those watching on YouTube, such as this one, of a five-woman protest against Morocco’s parliamentary elections last fall. One woman holds the flag of Sahrawi independence, while the others hold signs in Arabic, French, Spanish, and English stating “All Sahrawis are opposed to Morocco’s illegal elections in Western Sahara.”

Many protest videos show tactics of nonviolent resistance that demonstrators may have picked up from the American Civil Rights Movement and other nonviolent social movements around the world. This video, taken in July of a protest in Laayoune by unemployment activists, is one example.

While Moroccan security forces attempt to forcefully dismantle the demonstration, protesters link arms to resist, and attempt to continue their protest amidst the chaos.

Police Intervention & Abuse

Of the 81 protest videos curated in the past year, 51 were tagged with “police intervention,” 10 with “police brutality” and 8 with “injury.” Authorities intervened to disperse protests of any issue and size. The first minute of this video, filmed on a day of action by human rights activists across Laayoune last April, shows a common scene.

Three women unfurl a banner on a main street and begin chanting. Within 30 seconds, security forces run up and attempt to snatch the banner from their hands. When the women hold onto it, they are quickly outnumbered by uniformed and plainclothes officers who attempt to force them apart.

When protests have already grown to include dozens of activists, we often see security forces approach en masse, charging towards the protesters or pulling them apart with force to disperse the demonstration.

Security forces appear to be cognizant that their actions in public may be caught on camera, and they take steps to keep the most egregious abuses out of public sight, or conducted by plainclothes rather than uniformed officers. When protests are intervened, we often see activists forcefully removed from the scene. Because the filmers of these videos are usually hidden and at a distance from the protest, they cannot follow the action to record what happens next to these activists. (See, for example, this clip of an activist holding a Sahrawi flag removed from a demonstration in late last year.)

Occasionally, however, media activists record scenes of abuse that Moroccan security forces try to keep out of view.

At 3:50 into this video of a rally in November, we see plainclothes officers force several women into a side street, presumably where they think no one can witness or record their actions. There, mobs of men surround and attack individual women. Eventually, the filmer is spotted by the officers and the recording comes to an end. Injured protesters later described their experience to U.S. journalist Amy Goodman, who was in Laayoune at the time.

When abuse takes place behind closed doors, Sahrawi activists occasionally recount their abuse in video testimony. When women’s rights activists were arrested and detained at a march in August, several women gave testimony on video in which they described their detention and abuse behind bars.

The frequency of police intervention at peaceful protests in Western Sahara attests to a society with no tolerance for dissent. It’s no wonder Morocco has banned Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch from the territory, and cracks down on local and foreign journalists who report on human rights. They want to avoid the world witnessing the story of repression, intolerance, and abuse that we see in citizen footage.

Spotlight on Political Prisoners

One of the most common themes of videos we curated in the past year wasthe issue of political prisoners. Twenty-two of the curated protest videos were in regards to one of two high-profile cases — that of Brahim Saika, a leading Sahrawi activist who died while on a hunger strike in detention, and the defendants of the Gdeim Izik trial.

After the death of Brahim Saika — a leader in the movement of Sahrawi unemployed activists — at a Moroccan hospital last April, protests throughout southern Morocco and Western Sahara called for an investigation and characterized his death as the latest indication of a pattern of abuse and neglect of Sahrawi political prisoners. (You can see a roundup of many of these videos on the Watching Western Sahara Stories page.)

Meanwhile, the civilian trial of the “Gdeim Izik group” began. For six years, 24 Sahrawis have been in jail for their alleged participation in the Gdeim Izik protest camp — a massive encampment in late 2010 protesting conditions under occupation that turned deadly when it was dismantled by Moroccan forces. They have gone on hunger strikes and have inspired protests in Western Sahara and calls for their release by organizations around the world. In 2013, a Moroccan military court sentenced them to 20 years to life in what Human Rights Watch described as “seriously flawed trials.” A Moroccan court later nulled those convictions and sentences and referred the case to the civilian Court of Appeal in Rabat. That case began on December 26, and was followed by international observers. Protests by Sahrawis in support of the prisoners took place outside the courtroom and in occupied cities, including Laayoune and Smara, and many were caught on camera. After continuing in March, the trial is now on pause until May.

Sahrawi political prisoners who are tried in Western Sahara rather than Morocco have a harder time gaining international attention and support, due to Morocco’s common practice of expelling foreign activists, reporters, and researchers from the territory. On December 20, for example, two Spanish lawyers were expelled from Laayoune and prevented from attending the trial of two Sahrawi activists.

Methodology

This report was compiled by the international Watching Western Sahara team based on videos curated and contextualized on the Watching Western Sahara Silk platform. The majority of the videos curated were filmed and shared by Sahrawi journalists, citizen journalists, and media collectives based in the occupied territory. Each video has been verified and contextualized based on information in the video, reliable online sources, and individuals familiar with the scene. These videos represent only a fraction of all videos recorded in Western Sahara from April, 2016 through March, 2017, and give a limited snapshot of human rights abuses that took place during that timeframe. For more information on Watching Western Sahara, see the About page on Watching Western Sahara.