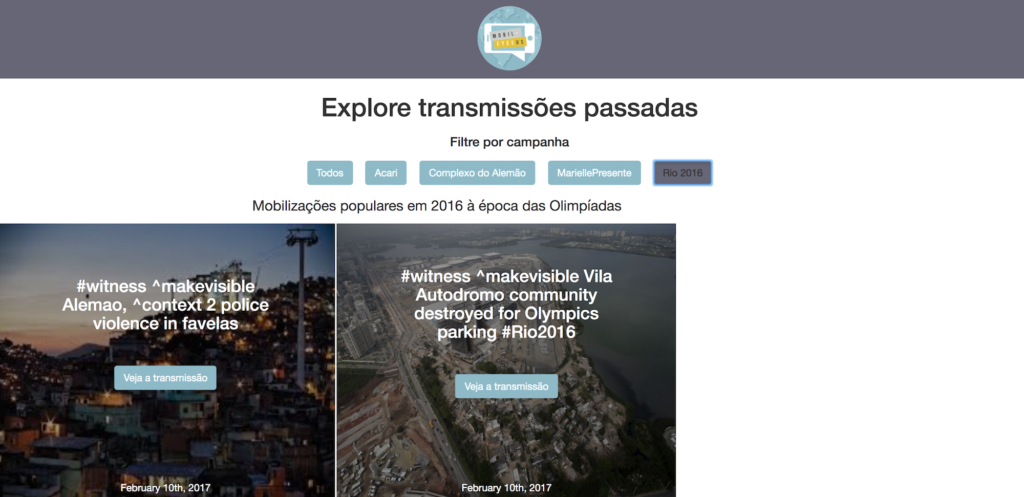

Mobil-Eyes Us is a project of WITNESS and the WITNESS Media Lab to explore potential new approaches to livestream storytelling for action. We look at technologies, tactics and storytelling strategies to use live video to connect viewers to frontline experiences of human rights issues they care about, so they become ‘distant witnesses’ who will take meaningful actions to support frontline activists. We have developed a series of storytelling experiments, in collaboration with favela-based human rights activists in Rio de Janeiro, which has lead to an app. This app, Mobil-Eyes Us (which is in its alpha stages), enables an activist group to curate a series of eyewitness Facebook livestreams and push these to the relevant people in their network to watch and take individual or collective action. They would be able to rapidly share a stream so more people are present and witness an incident, help translate, provide guidance or give context.

These blog posts are part of our exploration of effective new approaches to livestreaming storytelling, the technologies that can support this and how both can be linked to effective ‘distant witness’ action around livestreamings as part of the Mobil-Eyes Us Project at WITNESS and the WITNESS Media Lab.

By Clara Medeiros, Adriano Belisário and Eric French

Mobil-Eyes-Us teaches us that a series of live broadcasts can form (and be formed by) many layers composing a rich story arc that tells us more than one individual stream can. So we explored ways to present a series of live videos combined with the context created through the active forms of participation depending on different abilities and availabilities of distant collaborators. Our assumption was that the more people know about the “big picture” ( a local group’s larger story of struggle), the higher the chances of their active and meaningful involvement.

Since the first phase of Mobil-Eyes Us (MEU) in 2016 we wanted to have a series of informative videos about the history of communities affected by the Olympic Games (and by the broader patterns of violence that existed in the lead-up) that could be shared to build a more complete understanding of resident experiences. These videos individually could give a glimpse of their reality, but can also serve as a piece of context on previous or future streams.

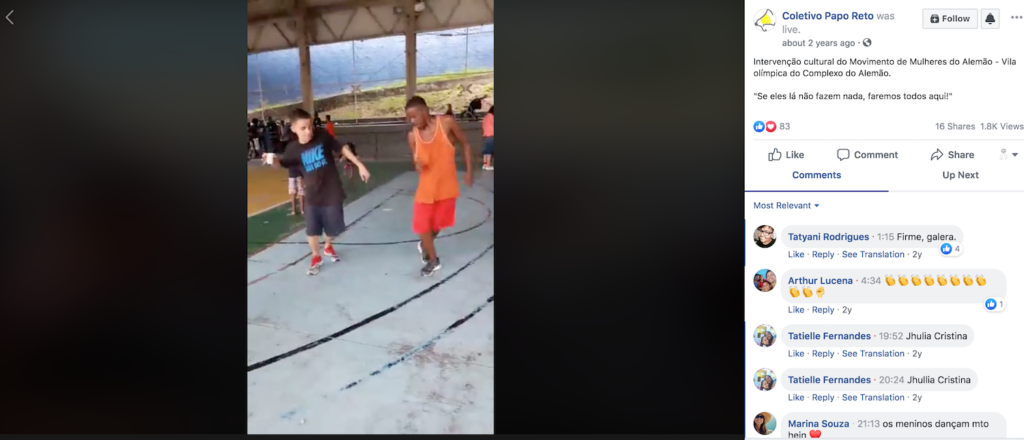

Favela Skol is part of Complexo do Alemão, one of the main favelas of Rio de Janeiro. Here’s how we engaged audiences in ‘co-presence’ during live streaming:

1) INTRODUCING A COMMUNITY’S HISTORY

In this first video we presented details about Complexo do Alemão’s history:

Thainã de Medeiros, from Coletivo Papo Reto,summarizes the area’s history and giving information about the terrain, the occupation of the land and the supposed reasons for the eviction. He also talks to residents about their personal stories, and familiarizes the audience about a series of actions they had done before and during the Olympic Games Collaborators engaging with the MEU process remotely have a solid base of knowledge to work with and can start including links and information in the comment sections from the streamings that followed on that day.

During the second live video of the day it was also possible to add to what they said in the broadcast comments with links like:

- examples from Coletivo Papo Reto publications documenting the previous actions of these residents;

- examples from publications by other local activists that had documented previous actions;

- an online petition made by residents to pressure the Governor of Rio.

Thainã gives more details about the eviction process in the third live streaming. He also interviews Cristina, a resident who lost her home due to landslides during the heavy rain season at Pedra do Sapo, a favela within Complexo do Alemão, between the years of 2009 and 2012, which was the same period that evictions happened at Favela da Skol. We then summarized what had been presented in the comment section for further context, including the link to the residents’ petition and a link to the article from Rio on Watch about Skol’s eviction.

In the fourth and last live stream of the day, we continued Cristina’s interview, and also learned from Camila, a resident and well-known activist of Skol’s struggle, that there would be a planned action on Copacabana beach the following Sunday, the last day of the Olympic Games. In addition to updating the comments with summary and context, we also added a link to the Facebook page maintained by Camila so that people could connect with her directly. We referred our followers to live.witness.org both during the narration of the broadcast as well as in the post’s comments.

2) REINFORCING THE ARC

We created two Facebook events, one in English and one in Portuguese, to publicize our previous broadcasts as context to Camila’s planned action at Copacabana beach during the closing day of the Rio Olympic Games . However, because of bad weather, the action was canceled, so we decided to update the respective Facebook event pages accordingly.

With the update, we also gave a notice that in 8 days there would be a public hearing where Favela Skol residents and other evicted Rio communities would demand officials honor the promises made of compensation for their evicted homes and new housing with concrete dates to begin construction work.

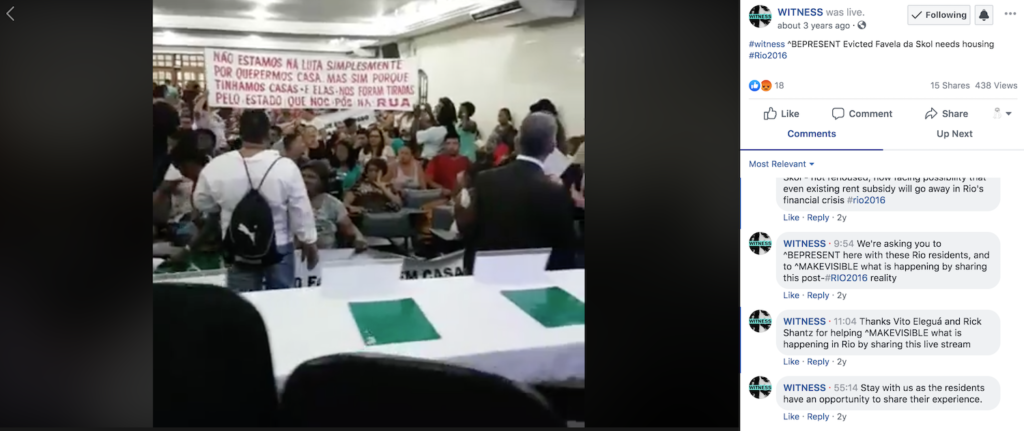

MEU also created events on Facebook(in English and Portuguese) for supporters to accompany the hearing remotely through a livestream. During this livestream above of the hearing, Camila confirms that the leaderships from Pedra do Sapo, Itaoca, Skol and Palmeira are present. Tactically, it is important make it clear that leaders are present and are always willing and open to dialogue with responsible institutions and to have this documented to keep records straight.

We were able to remotely follow the public audience and hear their demands through a series of four live broadcasts that included narration and translation in English via a MEU participant watching remotely. Public hearings are often events where attendees have strongly differing opinions, but this specific one was louder and more frustrating than usual. Because the reserved room was so full, many residents who had attended to follow the frustrated attempts to hold state institutions accountable had to watch the hearing from a separate room.