Mapping the Dead in Ethiopia

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the second post in our Curate for Justice series, profiling and sharing lessons from innovative documentation and advocacy initiatives—specifically those which curate eyewitness media to monitor a human rights issue. If you work on such a platform yourself, we’d love to hear from you. Click here to learn more.

In November, 2015, people in Ethiopia’s Oromo province rose up in massive protests. It was the second time in two years that activists demonstrated against the government’s plan to expand the capital and displace farmers who belong to the large but politically marginalized Oromo ethnic group.

The government’s response was brutal. Human rights groups condemned the crackdown, which included the use of live bullets, smoke bombs, arrests, torture, and censorship.

But when it came to quantifying the state’s repression and counting the protesters killed, the numbers ranged dramatically depending on the source. According to Human Rights Watch, 140 peaceful protesters were killed in two months of protests, while the government acknowledged just five deaths. Meanwhile, hundreds of images of demonstrators allegedly killed or tortured circulated on Facebook, often with little or no information about the source or the context.

The combination of citizen reports, social media, government-sponsored trolls, and misinformation contributed to a fog of war—a muddling of basic facts that could jeopardize any chance of justice or accountability.

Following the story from Eugene, Oregon, exiled journalist and academic Endalk Chala saw a need to not only share the news from home, but to verify, contextualize, and track online reports.

“My objective,” he explained recently, “was to document and give names to people who were killed.”

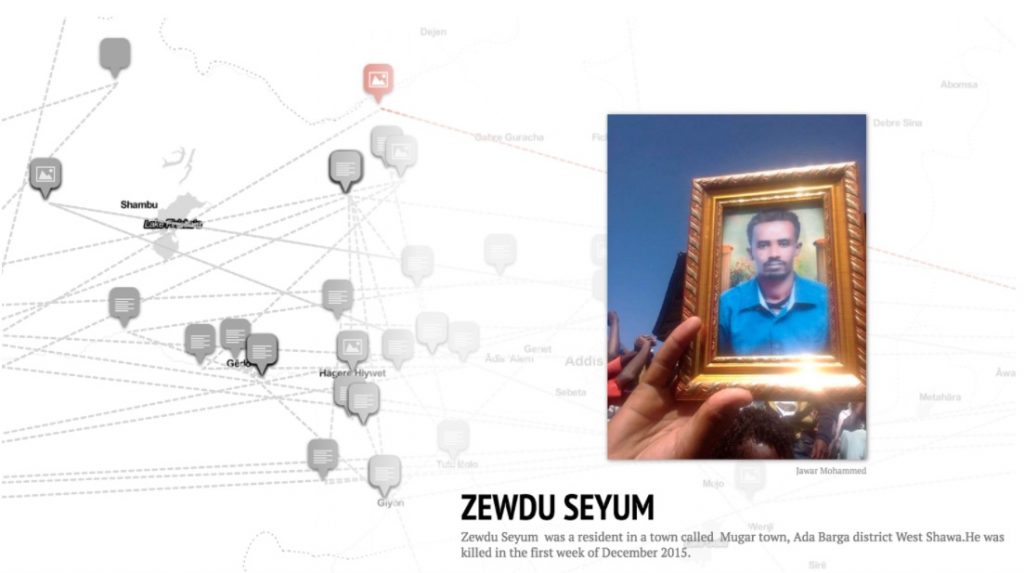

So began “Mapping the Dead in Oromo Protest,” the only public database of verified deaths by Ethiopian security forces in Oromia. Using a combination of social media reports, traditional fact-checking, and an online mapping platform, Chala created a unique source of verified information on an issue inundated with factual discrepancies. The map includes more than 120 entries, each listed by location and date of the person’s death. Most were killed over just a few days of protests in December, 2015, and others during a traditional festival the following October, when security forces used live bullets and smoke bombs on an Oromo holiday celebration, causing a deadly stampede. When available, the entries include a photo of the individual in their lifetime, in their death, or of their funeral.

Since Chala launched the map in early 2016, the protests have continued—widening their focus to address various issues of justice and equality for the Oromo people—and so too has the government’s repressive backlash. While Chala has not updated the map since late 2016 due to limited resources, he continues to track alleged killings—including the reported deaths of 10 protesters the day before we spoke—and attempts to verify and archive his findings. Now nearly two years in, his experience documenting deaths in Oromia offers lessons for others using social media and online tools to document human rights violations.

Background

Chala, an editor at Global Voices, has written extensively on the roots of the Oromo protest movement, and the government’s deadly crackdown on protesters. Reporting on an Ethiopian protest movement calls for unique approaches to fact-finding. The country is among the most restrictive media environments in sub-Saharan Africa. Critical journalists and bloggers risk arrest and persecution, leading to one of the highest number of exiled journalists in the world. Chala himself, a co-founder of the Zone 9 blogging network, was forced into exile in 2013, and many of his colleagues have been imprisoned.

In a context of censorship, attacks on the press, and a lack of local independent media, citizen reports fill a critical gap in exposing the massive demonstrations and violent government crackdown. When protests broke out in late 2015, activists shared videos of demonstrations and police violence on Facebook. Footage showing security forces shooting into crowds of peaceful demonstrators circulated among Ethiopian journalists and news outlets working in exile, some of which then broadcast the footage back into the country via satellite TV, which the government attempted to block.

But as Chala explained, “there must be a verification process,” and that process is rarely a part of this rapid, global, and often politicized circulation of news. He has seen activists and diaspora news networks share exaggerated, manipulated, and false reports of abuse. “Yes, it is repressive,” he says. “I am a victim of the government. But I think it’s important to ground our discourse in facts.”

When available, images of the life, death, or funeral procession of those killed are included in the entry.

Chala developed his a methodology for finding, verifying, and mapping reports of those killed, which goes like this:

- Discovery: Find reports on social media, often from the accounts of exiled journalists and satellite TV networks. Download photos and videos.

- Verification: Contact the original source, or sources on the ground, to verify or debunk allegations of report.

- Add to database: If the report is verified with certainty, add to the online map on StorymapJS, a free online mapping platform developed by the Knight Lab.

Throughout this process, he’s learned a few tips for verifying online media in a context of political conflict and misinformation.

1: Verify, verify, verify

Chala’s understanding of the conflict, his fluency in local languages, and his network of reliable sources on the ground are key. So too is his vantage point far from Ethiopia, allowing him to ask questions about footage circulating online that he wouldn’t be able to if he were under the watch of authorities.

When he comes across a report of deadly violence against Oromo protesters, he attempts to track down the original source of the footage or someone who witnessed the event firsthand. Using social media and secure communications, “I ask them, where did you take it? Who took it?.” Only after he confirms that the event occurred as reported does he add it to the map. “If I talk to people and they sound fishy, I will leave it out.”

2: Beware the Trolls

In Ethiopia, there is a term for paid internet trolls: “kokas”—an Amharic word referring to people who sell themselves for easy money. They often find footage from Arab countries or sub-Saharan Africa, “and put it on social media, saying (Ethiopian) government forces have killed protesters.” The pictures are brutal, and many journalists in the diaspora fall for them.

Why would the government support false stories about state violence? Once the reports are picked up by opposition or diaspora news outlets, “the government takes that in state media and broadcasts it, saying they are liars.” The objective is to sow doubt and confusion, and undermine the credibility of independent media.

“These kokas, most of them are anonymous. They will even send you videos, or links, saying ‘have you seen this? The government is doing this.’ You have to be very careful.”

In one case, images circulated showing two dead bodies on the street. A prominent diaspora news outlet wrote a story about it, saying that they were executed because of their political opinion. Government sources said they were executed because they were armed criminals. By asking his sources on the ground, Chala found that there was no protest in the area where the picture was taken, and that those killed were, in fact, alleged criminals with no ties to the protest movement. Ethiopian state media accused the diaspora news outlet of false reporting.

3: Time is a Verification Tool

Misinformation trolls, and the sensational stories they disseminate, feed off the 24/7 news cycle—constantly seeking eyeballs and reaction from viewers.

“So I wait,” says Chala. Time is one of his most valuable tools in fact-checking online reports. Within a news cycle, there is pressure by sources to magnify a conflict, and pressure by the media to sell a story and stand by it. But once the media has moved on, there is less pressure to sell a particular narrative. By simply waiting before he researches any particular allegation, Chala has an easier time determining the facts.

4: Protect Sources

As an exiled blogger, Chala knows the lengths the government will go to target journalists and those providing them with information. There are a few steps he takes to minimize the risks to his sources on the ground. First, when seeking corroboration about a particular event, he often writes as much about it to his sources as possible, to minimize the amount of information that his interlocutor would have to provide. “Just let me know if this person was killed at this particular time in this particular place. Yes or no.” He uses secure communications, and with his closest sources, he has a security plan in place in case anything happens to them or their devices. Fortunately, he hasn’t had to use it.

Mapping the Dead in Oromo Protest is a brutal document of a protest movement and the repression it has faced. Chala acknowledges that there must be many more deaths than those he has been able to verify. But he can stand by every one of the cases in his database, and he hopes that in the long term, the map will help bring justice for those killed. “It may not be in my lifetime, but sometime in the future, somebody will be responsible for this. And if I do this with integrity, they will be exposed.”

To explore “Mapping the Dead in Oromo Protest, click here (WARNING: the database contains disturbing images. You can follow Endalk Chala’s continued reporting on the protest movement in Oromia on Global Voices.