Published October, 2018 by WITNESS in Uncategorized

Trapped in the Gulf: Exposing Migrant Abuse

This post is part of the WITNESS Media Lab’s new project, “Perpetrator Video in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)”. This project examines how human rights advocates and journalists can turn the proliferation of eyewitness and perpetrator video into more ethical and effective storytelling and documentation of human rights abuse in the MENA. Follow along each month as we share resources, case studies, and more to strengthen and protect communities against harm through safer, more ethical and more effective use of video in contemporary reporting and advocacy in the MENA.

“For any mistake, she would hit me with her hands, a knife, scissors, sticks and sometimes bite me, pull my hair and other times pour boiling water on my body. I came to this country in good health, and now I return home with a disability. I just want to go home.”

A 28-year-old Indonesian housekeeper living in the United Arab Emirates

Source: The Washington Post

By Raja Althaibani

The proliferation of eyewitness and perpetrator video presents a unique challenge for journalists and human rights defenders. While we want to use them to enhance our understanding and reporting on perpetrators’ human rights violations, we do not want to further the objectives of the abusers.

This difficulty is particularly acute when reporting on migrant abuse in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, where there is a persistent lack of data, fact-checking, and little understanding of the context of crimes. Perpetrator video of abuse against migrant workers has emerged as a source of information of the violations they face, but how to use this content ethically hasn’t been widely explored until now.

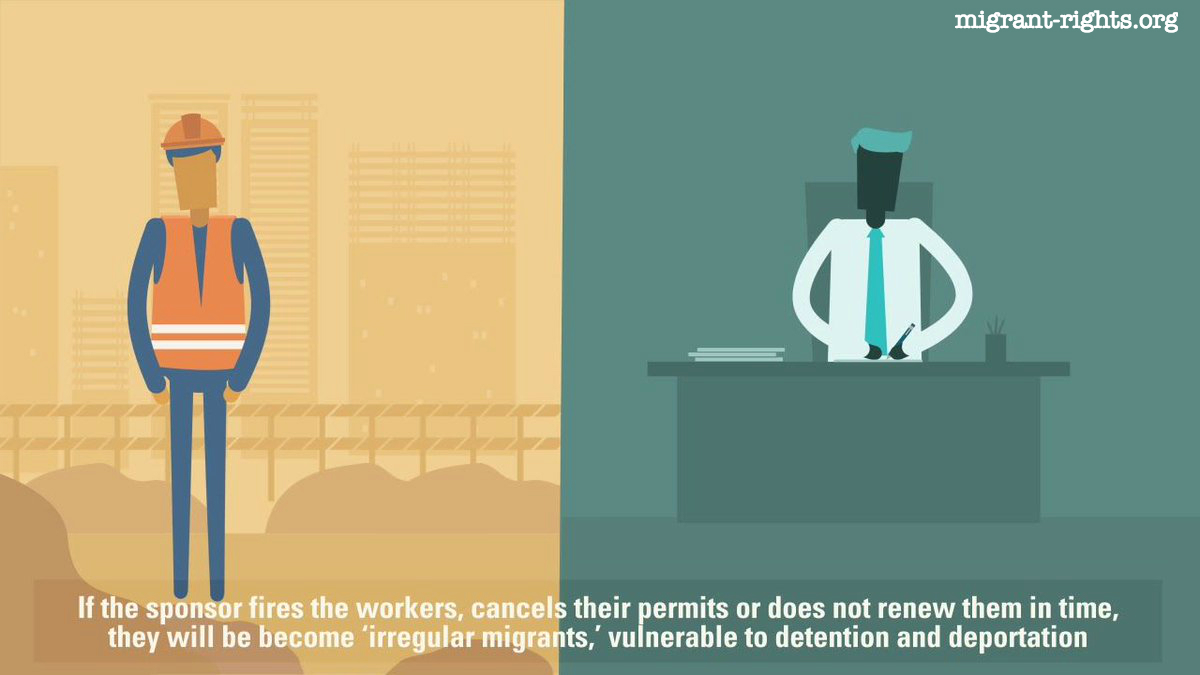

Migrant abuse under the Kafala system

Migrant workers comprise nearly half the population of the GCC countries and nearly 90% of the workforce in some states. However, their working conditions are unfair and often inhumane. Migrant laborers are sponsored in the GCC under the kafala system, through which they are required to have an in-country sponsor, usually their employers who are responsible for residency permits, work visas, and even the permission for workers to exit the country and end employment. The system often renders temporary workers completely dependent on their employers’ will. This systematic disempowerment leaves workers at the mercy of their sponsor. Many migrant workers have their passports confiscated by their employer, and domestic workers are often isolated in their homes and forced to work without a day off. This makes it more difficult for them to escape–or even alert authorities–about abusive conditions.

If migrant workers attempt to escape from an abusive or unsafe working environment, they can be charged with absconding, which in most GCC countries carries a jail sentence. Most migrant workers cannot change jobs without their employer’s permission or an extremely protracted process, which in an already abusive situation leaves them susceptible to further abuse with few options to escape.

While employers have been accused of abuse—sometimes to the point of murdering an employee—authorities rarely prosecute them, dismissing migrant workers’ allegations as anecdotal rather than evidence of systematic violence. Low-income migrant workers rarely receive justice through the legal system.

Eyewitness video can be crucial for documenting crimes against migrant workers, generating public outrage, and putting pressure on legal proceedings. These videos can support migrant workers’ testimonies, be used by journalists and human rights defenders in their investigations of abuse, and by prosecutors in order to build cases against abusers. Ultimately they can be used to demand reform of the kafala system, enforcement of labor/domestic workers’ laws, and improved grievance mechanisms.

In some cases, a short video can serve a witness to a crime that is otherwise anecdotal and unproven. Metadata embedded in most cell phone video can provide additional information on where and when the crime took place, and, in some cases, who committed it. When the video is filmed by the perpetrator themselves, it can provide rare access to information regarding who the abusers are, and who else is involved.

Dilemmas of using perpetrator video to expose migrant abuse

But what should we, as journalists and human rights defenders, be aware of when using one of these videos as a source or human rights documentation, or, further yet, posting it? Is our access to content (and our understanding of it) limited? What is the context of the video, and how can it be used to further collective understanding of a certain issue, such as migrant abuse, as a whole? Does the video show the victim breaking the law (such as absconding) in a way that could ultimately be used against them? Could sharing the video ultimately do the victim more harm than good?

In collaboration with Migrant-Rights.org, in the upcoming use cases we examine the role and impact of perpetrator video in exposing and perpetuating abuses against migrant workers in the GCC and will highlight best practices and key considerations for human rights defenders using this type of video to research and report on abuses against migrant workers.

We will explore several different cases where journalists and human rights defenders used perpetrator videos to shed light on human rights abuses, what each achieved, and what each could have done better in order to shed light on this issue.

Stay tuned as we analyze in our next installation how a viral snapchat video was covered by media and how we can take ethical and safety considerations into account to get to the facts and understand its context. For now, be sure to explore Migrant-Rights.org’s interactive narrative, Life under Kafala: A Migrant Worker’s Perspective, below.