What Journalists Should Know Before Reporting on Border Communities

This post was written by Michelle Serrano – Brownsville, Texas native, Communications Strategist at Voces Unidas (formerly called the Rio Grande Valley Equal Voice Network), and so much more. WITNESS is proud to partner with such a vital force for immigrant rights at the US-Mexico border, and we hope the information shared below can fortify our stories and make our resistance grow stronger.

In my time traversing social media, I have come across many discussion forums where I tend to share nuggets of wisdom regarding what border communities are like and how our communities are handling issues like immigration, law enforcement initiatives and an ever-increasing push for border militarization.Yet frequently I find this information to be discredited, disputed, or ignored. For example, when I shared that the Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe had initiated a “No Border Wall” initiative to protect their ancestors and cultural artifacts at the National Butterfly Center, I was rebuffed with responses like “they aren’t a federally recognized tribe.” When I shared a press release regarding the New Year’s CBP tear gas attack , the statement was diminished as “cultural legend,” as a reader so coined my testimony. According to the self-described journalist’s response, how could my information even be truthful if the national and trusted media was not reporting the information I had to share about the community where I live, the Rio Grande Valley (RGV)?

I balked at the idea that they questioned the veracity of my own community and the issues we face. Residents of RGV, which have historically experienced generations of marginalization thanks to colonialism, industrialization and racism, are further victimized by the fast deadline reporting of parachute journalism and the fragmented information the rest of the country subsequently absorbs about us.

What We Wish Reporters Knew

The border has always been what is best described by writer and Harlingen, TX native Gloria Anzaldua, as “una herida abierta,” or “an open wound.” As we struggle to heal from the years of damage imposed by a society’s embrace of Manifest Destiny at the border, we have garnered unique experiences and perspectives that are representative of the duality of two cultures coming together as a community. It’s precisely because of this that we encourage the media to take better care in its portrayal of our beloved home by following some simple guidelines:

Our Communities Deserve Fair Representation

Be thoughtful about how you visually represent the border through your visual storytelling. We are not a “no-man’s land” that a wall will have little impact over or an ongoing scene from “Border Wars.” On the contrary, the river has played a historic role in our region, not just for agriculture, but for the way we live. The RGV enjoys a rich quality of life and history abutting the river that features conjunto concerts (traditional South Texas dancehall music,) palm tree forest preserves, Native American burial grounds, the last weigh station for the underground railroad before crossing the Mexico border, barns of farm animals and historical inter-faith missions.

Be thoughtful about how you visually represent the border through your visual storytelling. We are not a “no-man’s land” that a wall will have little impact over or an ongoing scene from “Border Wars.” On the contrary, the river has played a historic role in our region, not just for agriculture, but for the way we live. The RGV enjoys a rich quality of life and history abutting the river that features conjunto concerts (traditional South Texas dancehall music,) palm tree forest preserves, Native American burial grounds, the last weigh station for the underground railroad before crossing the Mexico border, barns of farm animals and historical inter-faith missions.

Militarization of our ecosystem with something like a border barrier will destroy quality of life and cultural touchstones for our communities. Make sure your photojournalism and curation of images reflects that reality. If there is ever any doubt of how we prefer our community to be depicted, look no further than the journalism of our local news sources like The Brownsville Herald and The Monitor. While they may not always be invited to press junkets Customs and Border Protection(CBP) holds for national media, they are entirely capable of connecting the human impact to the national headlines. As a final note, be courteous to immigrants and their families and ask before you take their photos. When an image of a vulnerable family goes viral online, it exposes these individuals and their community to harassment. For guidance on how to share images safely and ethically, visit WITNESS’ Ethical Guidelines resources.

There are Actual People Behind The Headlines: We Should Treat Them As Such

Stop using the terms “illegal,” “illegal immigrant,” “illegal migrant,” or any variation of those words. The AP stopped using those phrases in 2013 saying that they would not longer sanction the use of “illegal” to describe any persons. And yet it still gets circulated by major media outlets. When it’s used, it not only dehumanizes and criminalizes people, but its use is a political statement as well. Please use terms such as “undocumented immigrants” or “undocumented people” for residents when at all possible. If they are asylum seekers or refugees, please make that important distinction. Also, don’t repeat hyperbolic rhetoric about border crossings – even if the administration says it, because it affects the general well-being of latinxs dealing with the fallout.

Stop using the terms “illegal,” “illegal immigrant,” “illegal migrant,” or any variation of those words. The AP stopped using those phrases in 2013 saying that they would not longer sanction the use of “illegal” to describe any persons. And yet it still gets circulated by major media outlets. When it’s used, it not only dehumanizes and criminalizes people, but its use is a political statement as well. Please use terms such as “undocumented immigrants” or “undocumented people” for residents when at all possible. If they are asylum seekers or refugees, please make that important distinction. Also, don’t repeat hyperbolic rhetoric about border crossings – even if the administration says it, because it affects the general well-being of latinxs dealing with the fallout.

In terms of asylum, international law states that everyone has the right to seek it by any means necessary (including coming to the country in between ports of entry). Just because, for whatever reason, someone did not make their case for asylum at a point of entry (POE) does not make them an “illegal migrant.” Also, existing walls in the RGV are not on the river and thus, those asylum seekers who cross are legally entitled to request asylum, wall or not.

Lastly, avoid the use of “illegal border crossings.” The term obscures the important complexities in immigration and asylum law. Instead, use “entries without inspection” or “unauthorized entries” or be specific as to the types of crossings you are writing about. Asylum seekers entering between ports of entry and migrants crossing without authorization to seek work or reunite with family are completely different immigration experiences. Each of these labels tells an important story that is erased when we say “illegal.

“La Jaula de Oro” (The Golden Cage)

Don’t forget that undocumented people have been peacefully living along the border for decades and those individuals live here, go to work and participate in community the same as everyone else–they just can’t do it anywhere else outside of the checkpoint perimeters (there are three in the RGV perimeters, the least known is the Boca Chica Beach checkpoint). We call this the “jaula,” or cage made famous through the Tigres Del Norte song, “La Jaula de Oro,” which details the heart-breaking, limbo-like status of southern border residents who are undocumented and for decades, have lived under the fearful shadow of family separation and deportation.

Generally speaking, if an undocumented person is caught and deported, they are barred from crossing again for 10 years. If they cross again, they are banned permanently (and will usually serve a prison sentence). This state of being is especially complex as families grow and acculturate as mixed-status households where parents, with luck and perseverance, may see their US-born children get married, get good jobs, and have children of their own.

Roots Break Walls

Our communities are actively participating in a resistance, though you may not see it in traditional terms. When you live in a poor community, showing up to an action sometimes means not showing up to work and then not having enough money for child care or food. Despite these factors, our region is civically engaged, with some neighborhoods holding some of the highest voter turnout in the state.

Our communities are actively participating in a resistance, though you may not see it in traditional terms. When you live in a poor community, showing up to an action sometimes means not showing up to work and then not having enough money for child care or food. Despite these factors, our region is civically engaged, with some neighborhoods holding some of the highest voter turnout in the state.

This is not a faceless cause either. Some of our strongest voices come from community Dreamers who bravely speak out in defense of other undocumented members of the community at great risk of targeted harassment and deportation themselves. What’s more, the media does not regularly cover our opposition as it does with CBP. Even during extraordinary circumstances such as taking part in one of the largest protests in the region during a presidential visit to McAllen, Texas (with over 1,000 people in attendance,) the action did not get ANY national coverage; just because the media isn’t covering our protests doesn’t mean they aren’t happening.

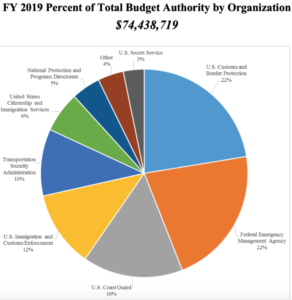

The Rise of the Border- Military Complex: Follow The Money

It’s important to contextualize who is getting money and profiting off of these decisions to militarize the border on all levels of government (and their respective contracting counterparts.) Additionally, please be conscious that before 2000 we were one community in spirit and existence, the Northern part of Tamaulipas, Mexico and the RGV; then we experienced 9/11 and everything slowly began to shift to a new era focused on “Homeland Security.” It created the impetus for border militarization (the border-military complex,) which was lucrative for the RGV, that suffered as a historically low income area with limited job prospects and a below average cost of living index.

It’s important to contextualize who is getting money and profiting off of these decisions to militarize the border on all levels of government (and their respective contracting counterparts.) Additionally, please be conscious that before 2000 we were one community in spirit and existence, the Northern part of Tamaulipas, Mexico and the RGV; then we experienced 9/11 and everything slowly began to shift to a new era focused on “Homeland Security.” It created the impetus for border militarization (the border-military complex,) which was lucrative for the RGV, that suffered as a historically low income area with limited job prospects and a below average cost of living index.

From DHS.gov

As a border patrol agent once joked with me when asked how work was going: “Well, I got job security.” He wasn’t lying. Ask what the subject of your interview gains directly or indirectly from their position or viewpoints regarding border militarization. In addition to the ballooning infrastructure of CBP and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), they have also acquired an agenda that is being directly prescribed to them by the White House. When journalists receive information from DHS, they are getting Trump’s talking points; question the data and framing, because it has a political agenda.

It’s important to compare government releases with the facts available to journalists. For example, if CBP puts out a press release stating that it had 400 apprehensions during zero tolerance implementation for federal immigration infractions, but there are not 400 petty crime offense complaints filed in federal court, it’s probably due to the fact that the people apprehended claimed asylum. It’s recommended that if journalists plan to run with a CBP Press Releases on apprehensions, they should cross check it with resources such as “PACER” to make sure they don’t contribute to the “invasion narrative” that the Trump Administration is vociferously spreading.

Our Resiliency Hinges on Continued Infrastructure Development and Capital Investment

We need improved infrastructure, not walls. The border has historically suffered persistent poverty, which has disproportionately affected the well-being and development of RGV children (who are predominantly Hispanic). The poverty rates have a direct correlation to the overall health of our communities, and there is a concerted effort to educate communities about nutritional health and prevent heart disease and diabetes.

We need improved infrastructure, not walls. The border has historically suffered persistent poverty, which has disproportionately affected the well-being and development of RGV children (who are predominantly Hispanic). The poverty rates have a direct correlation to the overall health of our communities, and there is a concerted effort to educate communities about nutritional health and prevent heart disease and diabetes.

Additionally, the region faces increased challenges with flooding, with stronger tropical disturbances wreaking havoc in an already flood-prone area. Walls would accelerate flood zones, but are prioritized for our area, leaving local counties to invest in drainage infrastructure improvements instead.

The facts remain that the RGV is drastically underserved in the national landscape, and militarization will only further undermine what little progress can be accomplished through local sales tax revenue. Finally the unique and exceptional environment of the RGV draws ecotourism dollars that would dwindle under the effect of militarized zones and lack of public access. We also must address the overall impression that border chaos rhetoric has on investors for our area. People will not invest in areas that are militarized, causing long term effects and sidelines to our community’s overall success.

Our Communities Have Endured Generations of Distrust

This isn’t new. The current administration is openly racist, but past administrations have also had horrible immigration policies. Just because a half-witted immigration policy changes back to existing policy (i.e. when we ended family separation), does not mean a crisis was averted, on the contrary, our communities are still in crisis with laws like SB4 that profile folks for being brown and poor.

Check points and border walls don’t just impact the natural border, they extend to create zones of enforcement that are 100’s of miles into the US interior, this undermines the constitutional rights of 2 out of 3 people living within the border zone. That means that only a third of folks are technically enjoying their full constitutional rights while the rest of us have to worry about getting profiled for looking suspicious, and let’s be honest – it’s definitely communities of color that get the worst end of the stick for that. If you’re headed out the RGV down Highway 281 to Brooks County, the largest checkpoint in the country can be found in the little town of Falfurrias, TX.

Don’t “Split the Baby in Two”

Courtesy of LUPE

When we come to a difficult impasse in negotiation about our communities, there is that inevitable question journalists ask elected representatives about “what exactly are they going to do to resolve these issues in a bipartisan manner,” without even considering the sacrifices elected representatives are asked to make on behalf of a nation far removed from the situation. This kind of question marginalizes us as a group and dilutes our power by reducing us to “an interest group” in our own homes. It’s not our job to compromise with campaigning politicians or the masses who know nothing about our communities. Just because someone comes up with a horrible policy idea and terrorizes our country with it (i.e. holding the government hostage for an impotent border wall,) doesn’t mean that we should comprise the best interest of our communities or stop telling the truth about our region. We can not be morally induced to bend to racism. On the contrary, it’s our duty to stand up for what our communities want and to make sure the truth is heard.

Repeat After Me: The Southern Border is Safe

The border is safe. According to the Wilson Center Mexico Institute, 22 of 23 counties are considered safer than other comparable counties in the interior United States. Even the staunchly Libertarian Cato Institute attests to the overall safety of our Southern borders, including the testimony of a border sheriff that states the frenzy and imagery of a border crisis is driven by politics and re-election concerns rather than real issues. Additionally, the Uniform Crime Reporting Data compiled by the FBI in 2017 indicates that only 19.4% arrests of Ethnic Hispanics have been reported across the nation, debunking the notion many politicians and conservative media float that the wall is needed to suppress crimes committed by undocumented people from Latin America.

How Can Reporters Ethically Approach Community Exchange About Issues?

Connect with local community organizations that work with low income people. More often than not they serve the same cross sections that are affected by negative border rhetoric. You can also look to the following examples of good reporting of our issues. The following are just a few examples, and many more are within this article.

Good Examples of Reporting

- Why Aren’t Texas Politicians Standing Up for Texas Landowners?

- In McAllen, immigration isn’t a problem — it’s a way of life

- Why We Need Mexico

- America’s poorest border town: no immigration papers, no American Dream

- Washington Trained Guatemala’s Killers for Decades The US Border Patrol played a key role in propping up Latin American dictatorships.

- A 5-Year Old Girl in Immigration Detention Nearly Died of an Untreated Ruptured Appendix

- Acupuncturists Without Borders to Hold Trauma-relief Clinic for Asylum-seekers and Volunteers

Additional Resources

- Opportunity Agenda Talking Points on Border Issues

- Three Narratives to Nix from your Immigration Reporting 2019

- Five Lessons for Shifting the Narrative on Migrants & the Border Region – Webinar from Opportunity Agenda (featuring speakers from CultureStrike and Alliance San Diego

- Eyes on ICE: Documenting Abuses Against Immigrant Communities – resources, case studies, etc. from WITNESS’ on how to use video to in immigrant rights work safely, ethically and effectively.

Michelle Serrano was born in Brownsville, TX, the southernmost tip of the the Rio Grande Valley. Michelle worked as a journalist and cartoonist at the University of Texas-RGV and received a BA in Public Service and Masters in Public Administration. She has actively participated in community advocacy campaigns that have fought for inclusivity in arts and musical institutions before her time as a communications strategist for Voces Unidas (previously called the RGV Equal Voice Network). The organization’s purpose is to motivate and uplift the voices of the community through integration and development of campaigns that improve the family outcomes of low-income communities.

Michelle Serrano was born in Brownsville, TX, the southernmost tip of the the Rio Grande Valley. Michelle worked as a journalist and cartoonist at the University of Texas-RGV and received a BA in Public Service and Masters in Public Administration. She has actively participated in community advocacy campaigns that have fought for inclusivity in arts and musical institutions before her time as a communications strategist for Voces Unidas (previously called the RGV Equal Voice Network). The organization’s purpose is to motivate and uplift the voices of the community through integration and development of campaigns that improve the family outcomes of low-income communities.

Photos: All photos were provided by RGV EVN unless stated otherwise